For this course, our main text is The Skillful Teacher: On Technique, Trust, and Responsiveness in the Classroom (3rd Edition) by Stephen D. Brookfield. This week’s blog assignment prompts us to comment on Brookfield Chapter 2, “The Core Assumptions of Skillful Teaching”. I have excerpted a quote from each of these four core assumptions to respond to.

1. Skillful teaching is whatever helps students learn

“If we simply mimic whatever teaching behaviours we endured as students (I suffered through it so now it’s your turn!) this won’t produce the results we want” (20).

I take it that here Brookfield is referring to the negative teaching behaviours we experienced as learners. This is certainly something I have observed in academia: the notion of paying dues, “rites of passage”, and literally cycles of violence in teaching. There can be a tendency to replicate a negative or even traumatic style because it was done to us and we believe this to be the only way to survive the system. just because an instructor is extremely knowledgeable about a subject and highly intelligent, does not mean that this knowledge and skill necessarily translates when it comes to engaging others.

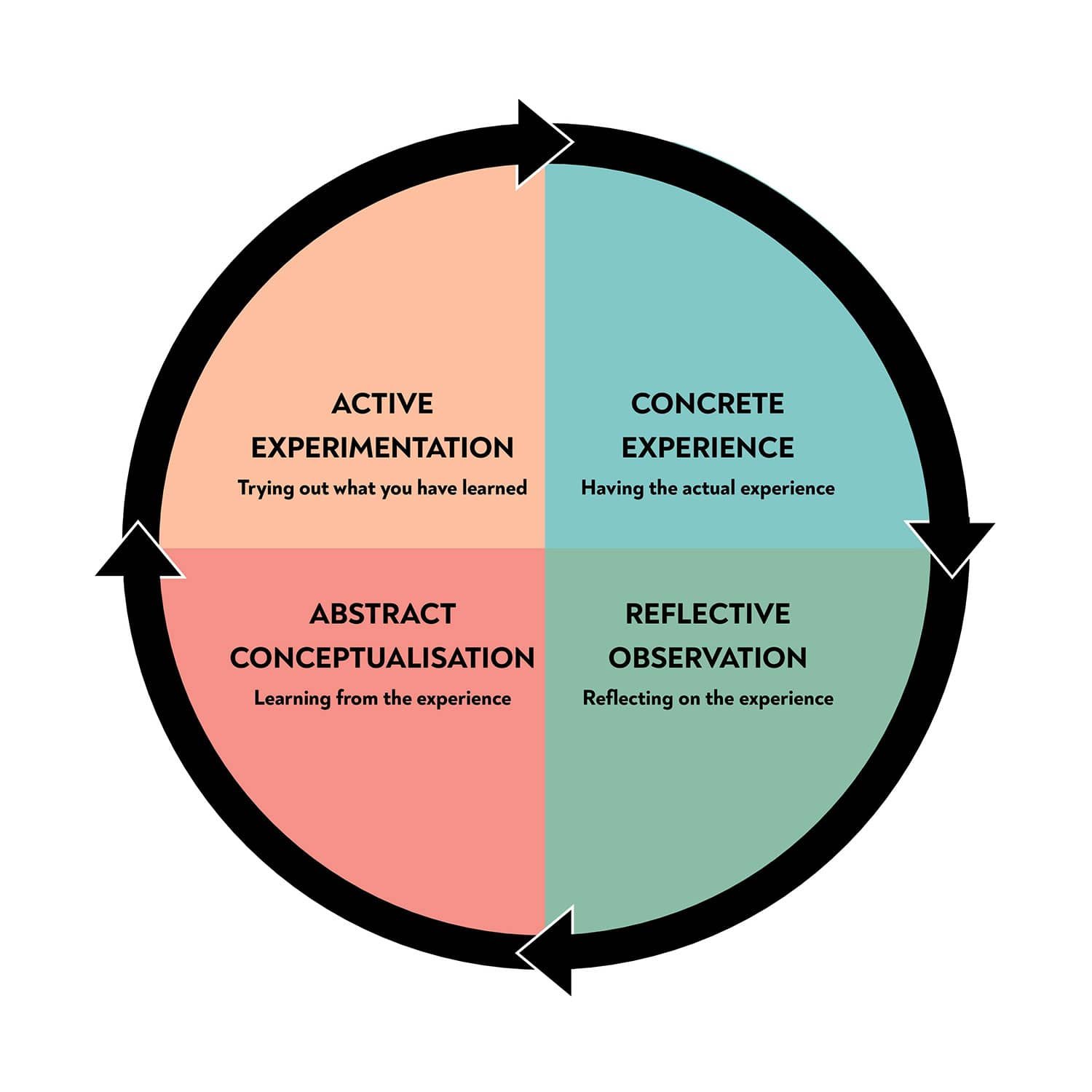

2. Skillful teachers adopt a critically reflexive stance toward their practice

A quote in this section is the antidote to the above: “Finally, reviewing our personal autobiographies as learners”… “helps us gain a better understanding of the pleasures and terrors our own students are experiencing” (20).

I think viewing our own autobiographies is helpful to a point, but as a teacher it’s also important to acknowledge the limitations of our own experiences. If I look at my own experience as a learner, I see someone who has felt largely confident and at ease in most educational settings. I have usually been able to build rapport with my instructors and fellow students, share my thoughts or ask questions in class (even if I felt a bit nervous, I could always push myself to do it), and complete work that met or exceeded the instructor’s expectations. There have even been times when I have felt comfortable taking initiative and asking instructors to modify an assignment so that it would be more interesting or challenging for me! I realize this is not the profile of a lot of learners. This is the profile of a lifelong nerd who knew from a young age that they wanted to work in education. I know that how I learn best and my own attitudes towards learning and education are not necessarily the same for all my students.

I try to model my own preference for instructors with a sense of humour and an openness towards creativity, while keeping in mind that not everyone learns like me and I may have to do things differently if my approach isn’t working.

3. Teachers need a constant awareness of how students are experiencing their learning and perceiving teachers’ actions

I agree with Brookfield that mechanisms for anonymous student feedback should be provided fairly early in the course. I teach 12-13 week courses, and I’ve done fairly basic anonymous surveys around Week 5 in the past. The questions I used were a) What about this course has been most useful to you so far? B) What about this course, if anything, could be improved? and c) Are there ways that you, the other students, or the instructor could make this course more effective? I would like to bring this practice back, but perhaps with different questions. I’m looking forward to reading about Brookfield’s Critical Incident Questionaire in the next chapter, an instrument which he says provides information about the “submerged dynamics and tensions that are either inhibiting or enhancing learning in [his] classes” (23).

“One of the most important indicators they mention that convinces them they are being treated respectfully is the teacher attempting to discover, and address seriously, students’ concerns and difficulties” (24)

4. College students of any age should be treated as adults

“[Students] often feel in limbo, sensing that adulthood means leaving old ideas, capacities, and conceptions of self behind as they learn new knowledge, skills, and perspectives. Sometimes it feels as if learning is calling on them to leave their own identities in the past.” (25)

I really like the emphasis on the impact of learning on identity. There can be a real crisis in learning, where we get stretched in new ways to the point of discomfort. Learning can bring up emotional responses. And of course, we’re never the same once we have been exposed to a new way of looking at something, or ourselves. But this is part of the process, and our balancing act as teachers is to provide a safe space for exploration while not coddling students to the point that they experience no discomfort at all.